Abstract

Rubiaceae is a plant family that produces several bioactive metabolites, including: indole alkaloids, triterpenes, iridoids, anthraquinones, among other. Among these species is Warszewiczia coccinea (Vahl) Klotzsch for which there are few chemical studies in the literature consulted. Considering this gap, the present study intended to deepen the phytochemical study and carry out evaluations of antimicrobial and antiangiogenic activities (chorioallantoic membrane assay). For phytochemical investigation, thin layer chromatography (TLC) and open column chromatography (CC) techniques were used and for chemical analyses, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). The results showed that methanolic extracts from the leaves presented antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans. The hexane extract of the branches showed antiangiogenic activity. Furthermore, hexane and methanolic leaf extracts caused toxicity at all concentrations evaluated in the angiogenesis assay. From the methanolic extract of leaves, it was possible to isolate the coumarin scopoletin. Furthermore, this extract showed an indication of the presence of other metabolites in 1H NMR analysis, such as terpenes and indole alkaloids. This is the first report of antimicrobial and antiangiogenic activity for W. coccinea and isolation of a coumarin for the genus Warszewiczia.

Antimicrobial; Antiangiogenic; Scopoletin; NMR; Alkaloids

Introduction

Plant metabolites still can offer compounds with important biological activities. The chemodiversity of these Natural Products may provide important molecular structures, some of them may be useful against microbial infections, resistant microorganisms, or human tumor vascularization1,2. In this context, phytochemical investigations may lead to the isolation and chemical characterization of these metabolites with biological activities3.

Brazilian plants have an important contribution to phytochemistry investigations4. Among these plants, species of the Rubiaceae family have some importance to Natural Products Chemistry. In the Amazon rainforest, this family ranks as the second-largest botanical family in the number of species 5. The main metabolites that occur in Rubiaceae species are alkaloids, triterpenes, iridoids, anthraquinones, and other classes. These metabolites have some biological activities and contributions to Rubiaceae’s chemosystematics6,7. Most alkaloids from this family have an indolic skeleton7,8, like monoterpenes indolic alkaloids found in Duroia macrophylla9-11. Additionally, other metabolites can be found like flavonoids and other classes12. Despite the chemodiversity of Rubiaceae, some species still lack chemical studies.

One of Rubiaceae genus is Warszewiczia, where there are few reports in the literature consulted. Only Warszewiczia coccinea, W. cordata, and W. schwackei showed chemical or biological studies13-17. For W. coccinea and W. cordata, there are results for antileishmanial activities, but the metabolites responsible for this activity remain unknown13,16. There’s been one report on the isolation of metabolites from W. coccinea: Calderon15 reports the isolation of two triterpenes: 6β,19α-dihydroxyursolic acid, and sumaresinolic acid which demonstrate activities on acetylcholinesterase inhibition. In W. schwackei can be found indolic alkaloids, highlighting the β-carboline alkaloids. Previously, we reported the antioxidant, antimycobacterial, antimalarial, and cytotoxicity activities of this species17. However, the few reports demonstrate a gap in the literature for the chemical characterization of bioactive metabolites from the Warszewiczia genus.

Aiming to increase the chemical knowledge and isolate bioactive metabolites from W. coccinea (Rubiaceae) we performed this phytochemical study. The present study is the first report of antimicrobial, antiangiogenic activity, and isolation of coumarin from leaves.

Material and Methods

List of reagents and equipment

Deuterated solvents (CDCl3 and DMSO-d6) were obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, USA. For chromatography experiments, was used Silica gel 60 (230-240 Mesh), Florisil (100 – 200 Mesh), and Thin-Layer Chromatography (20x20 cm commercial plates) were obtained from MERCK®, Germany. In antimicrobial assays, was used a Spectrophotometer for 96-well plate reading: Thermo Scientific, Multiskan GO. In angiogenic assays, an Egg incubator was used: Juli, Chocmaster®. NMR experiments were analyzed on a Bruker spectrometer (300 MHz), equipped with an EASYPROBE S1 5mm Z-GRADIENT. The Mass spectra were obtained in a Bruker Amazon Speed, Ion trap, and ESI ionization font. The Mass spectrometer is hyphenated on a liquid chromatographer Model Prominence UFLC (Shimadzu), luna C18 column, equipped with an LC-20AT binary pump, SPDM-20A diode array detector (DAD), and SIL-20A automatic injector.

Collection and Botanical identification

Leaves, branches, and bracts were collected from Warszewiczia coccinea, the plant material was collected in Campus I: Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, INPA (3°05’46’’S 59°59’17’’W on March 30, 2019). A voucher with fertile botanical material is available at INPA´s Herbarium (numbers 283507 and 285835). The plant collection has been registered on SISGEN (A85ED6B).

Plant extraction

The plant material was separated into leaves, branches, and bracts from the inflorescences, which were dried in a controlled temperature room. After drying, the samples were powdered in a knife mill. The plant parts were extracted with organic solvents in increasing order of polarity: hexane (Hex) and methanol (MeOH). Using maceration assisted on ultrasonic bath (40 MHz) for 20 min, adopting at least 3 extractions and obeying the proportion of 1 g of plant material to 3 mL of solvent (1:3, m/v). The extracts were concentrated in a rotary evaporator at a temperature < 50 °C.

Phytochemistry analysis by TLC and 1H NMR spectroscopic experiments

The crude extracts were analyzed by Hydrogen Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H NMR) operating at 300 MHz for 1H nucleus. For sample preparation, 20 mg of each crude extract was used and dissolved in 550 μL of deuterated solvents containing TMS for internal reference. CDCl3 was used for the hexanic extracts and DMSO-d6 for the methanolic extracts. The spectra obtained were processed and analyzed using Bruker® TopSpin software (v3.6.4). To aid in the interpretation of the spectra, data from the literature on the family's chemosystematics were used for the chemical characterization of the crude extracts.

In addition, the crude extracts were analyzed through Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) to previously detect the chemical classes present and evaluate the separation profile. The samples were eluted in appropriate solvent systems. UV light (λ: 254 and 365 nm) and chemical reagents like sulfuric anisaldehyde, ceric sulfate, ferric chloride, and Dragendorff reagent were used to indicate the classes of secondary metabolites in these extracts.

Isolation of scopoletin

Initially, the methanolic extract of leaves was submitted to liquid-liquid partition. Sample (19.72 g) was solubilized in a hydromethanolic mixture (MeOH/H2O 1:1, v/v), obeying the proportion of 1 g of sample to 50 mL of MeOH/H2O. Subsequently, the hydromethanolic phase was partitioned with Hexane (Hex), Dichloromethane (DCM), and ethyl acetate (EtOAc), respectively.

The DCM phase (FDCM, 1.5 g) was fractionated by column chromatography (h x ø: 5 x 8 cm) using silica gel, and as mobile phase Hex, DCM, EtOAc, and MeOH with an increasing gradient of polarity, starting with a mixture of Hex/DCM 1:1, yielding 12 fractions. The fractions 5-6 (36 mg) were refractionated by column chromatography (h x ø: 22 x 1,3 cm) using Florisil and as mobile phase DCM, EtOAc, and MeOH with an increasing gradient of polarity, starting with DCM 100%, yielding 39 fractions. The subfractions 30-32 (15 mg) were refractionated by preparative thin-layer chromatography using silica gel and as mobile phase DCM/EtOAc 95:05. After the elution, the plate was placed under UV light (λ: 254 and 365 nm), the band with Rf: 0,5 and intense blue fluorescence was delimited and removed from the plate. The resulting sample (3 mg) was analyzed by mass spectrometry coupled with liquid chromatography (LC-MS) and 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR, which allowed the identification of the scopoletin. In LC-MS the sample was analyzed in positive and negative mode with Electrospray source (ESI), with H2O (0.1% Formic Acid)/ACN (71.25: 28.75) elution system.

Antimicrobial assay

The microorganism strains used in this assay were: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA – Strain ATCC 10145), Candida albicans (CA – Strain ATCC 10231), Escherichia coli (EC – Strain ATCC 11775), Pseudomonas fluorescens (PF – Strain ATCC 13525), Aeromonas hydrophila (AH – Strain ATCC 7966), Klebsiella pneumoniae (KP – Strain ATCC 13883), Salmonella enterica (SE – Strain ATCC 13076), SM Serratia marcensces (SM – Strain ATCC 13880), Citrobacter freundi (CF – Strain ATCC 8090), Staphylococcus aureus (SA – Strain ATCC 12600). For this assay with natural products, the adapted guidelines that are recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute18 for in vitro antimicrobial sensitivity assays were used.

To determine the antimicrobial activity of the extracts, the microorganism inocula were standardized at 0.5 McFarland, then the standardized inocula were diluted (1:20) to be aliquoted for the assay. In a 96-well plate, 90 µL of each aliquot of extracts (1000 µg.mL-1 in Müeller-Hinton broth with DMSO 5%) was evaluated in triplicate. For negative control, the culture media Müeller-Hinton broth with DMSO at 5% was used. For positive control, 90 µL the antibiotic oxytetracycline was used (125 µg.mL-1in Müeller-Hinton broth). In each well, 10 µL of the aliquot of the standard microorganism inoculum was added.

Then, the 96-well plates were incubated at ± 37°C for 16 to 24 hours. The prepared plates were read in a spectrophotometer (λ: 625 nm) before and after the appropriate incubation. In the end, they were revealed with 40 µL of 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride solution in 2% (v/v), to verify cell viability. The results were submitted to analysis by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-test, comparing the samples with the negative control (CI of 95%, P value < 0.05). The data obtained were processed and analyzed with GraphPadPrism (v7.0) and Excel® software.

Angiogenic assay

The evaluation of antiangiogenic activity was performed based on the methodology described by Nguyen, Shing, and Folkman19 performed in the chicken egg (Gallus domesticus) embryo chorioallantoic membrane model (CAM). Using concentrations at 1000, 500, and 100 µg.mL-1 of the extracts diluted with ethyl alcohol, were implanted in methylcellulose discs, following the methodology described by Falcão-Bücker20.

Fertilized eggs were placed in an incubator, in the horizontal position (temperature 37.5°C and under 33% relative humidity). After 48 h of incubation, a small window of 5 mm diameter was opened in the shell, in the region of the air chamber of the egg, to aspirate 3 mL of egg white. The number of test eggs was in triplicate for each treatment and negative control. Another window of 15 mm in diameter was also opened in the region of the egg positioned above the region of the chorioallantoic membrane of the embryos and closed with black tape to minimize loss of humidity. The embryos remained under incubation, for another 72 h until the embryonic age of 6 days. At this moment, a methylcellulose disk (1.5%) embedded with extract samples, was placed over the chorioallantoic membrane, and implanted over the blood vessels in the external third of the chorioallantoic membrane. The orifice was again closed with the same tape. Incubation continued for a further 48 h, until the embryonic age of 8 days. For negative control, the methylcellulose disk was embedded in ethyl alcohol and dried.

For the analysis of angiogenic activity, the tape was removed to visualize the embryonic and vascular development around the disk implantation and was recorded a photograph for subsequent counting of blood vessels that were intercepted and near the disk (area of 0.9 cm2). The results were expressed in percentage of vessels ± standard deviation and compared to the negative control, the values were represented with the aid of GraphPad Prism software (v7.0).

Results and Discussion

Phytochemical analysis of crude extracts

The 1H NMR spectra of hexanic extracts of leaves and branches showed signals in dH 0.3 and 1.5, which are characteristic of methyl hydrogens that are present in the terpenes' structure. For both extracts, it is observed the presence of olefinic hydrogens in dH 5.36, 5.31, and 5.11, which are indicatives of the presence of the common plant steroids: b-sitosterol and stigmasterol21,22. In the aromatic region between dH 6.0 and 8.0, both extracts showed low-intensity signals, demonstrating that in the crude hexane extracts the phenolic or aromatic metabolites were not observable by 1H NMR analysis.

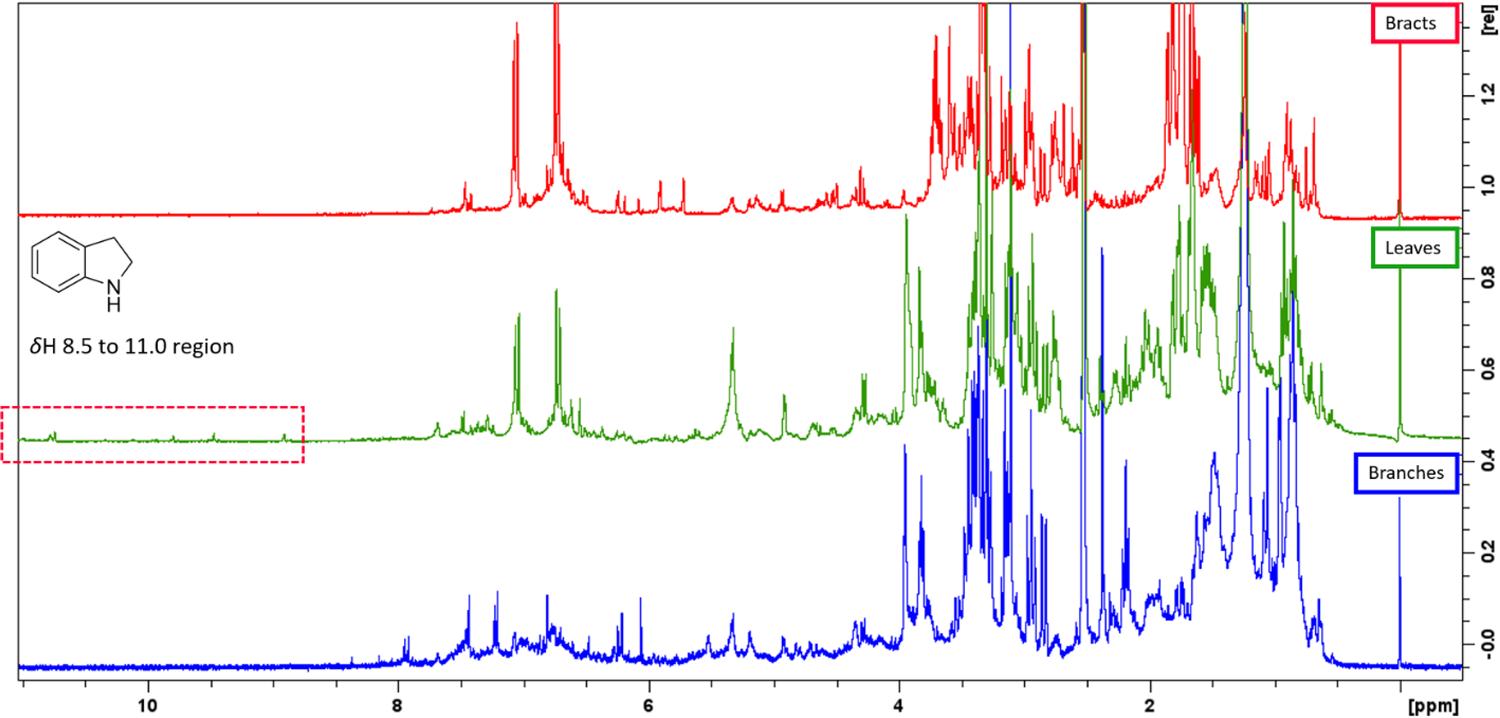

The methanolic extracts of leaves, branches, and bracts showed some spectral similarities among the signals. Signals in dH 0.3 to 1.5 are characteristic of methyl hydrogens that are present in terpenes. Observed multiplets signals in dH 3.0 to 4.0 may be related to free sugars or linked to other metabolites, and in dH 4.0 to 5.5 were observed indications of anomeric hydrogens. In the aromatic region between dH 6.0 and 8.0, were observed signals that suggest the presence of a phenolic, aromatic ring, or metabolites with conjugated double bonds, like flavonoids, coumarin, and other aromatics metabolites. However, only methanolic extracts of leaves showed hydrogens in dH 10.77, 10.73, 9.79, 9.46, 8.90, which is also indicative of chelated hydroxyls, aldehydes, or nitrogen-bonded hydrogens of indolic alkaloids. In TLC analysis, the crude extract of leaves showed non-reactive with Dragendorff, although the FDCM from this extract showed orange reactive spots with Dragendorff reagent, supporting the indication of alkaloids in the extracts. There is only one report of indolic alkaloids in the Warszewiczia genus17, some indolic alkaloids in Rubiaceae species can exhibit signals of the nitrogen-bonded hydrogens between dH 8.5 to 11.0 region on 1H NMR spectra7,10,11,17. This suggests that this chemical class may be present in the methanolic extracts of Warszewiczia coccinea leaves but at lower concentrations (FIGURE 1).

: 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) spectra of methanolic extracts of leaves, branches, and bracts of W. coccinea.

Identification of scopoletin

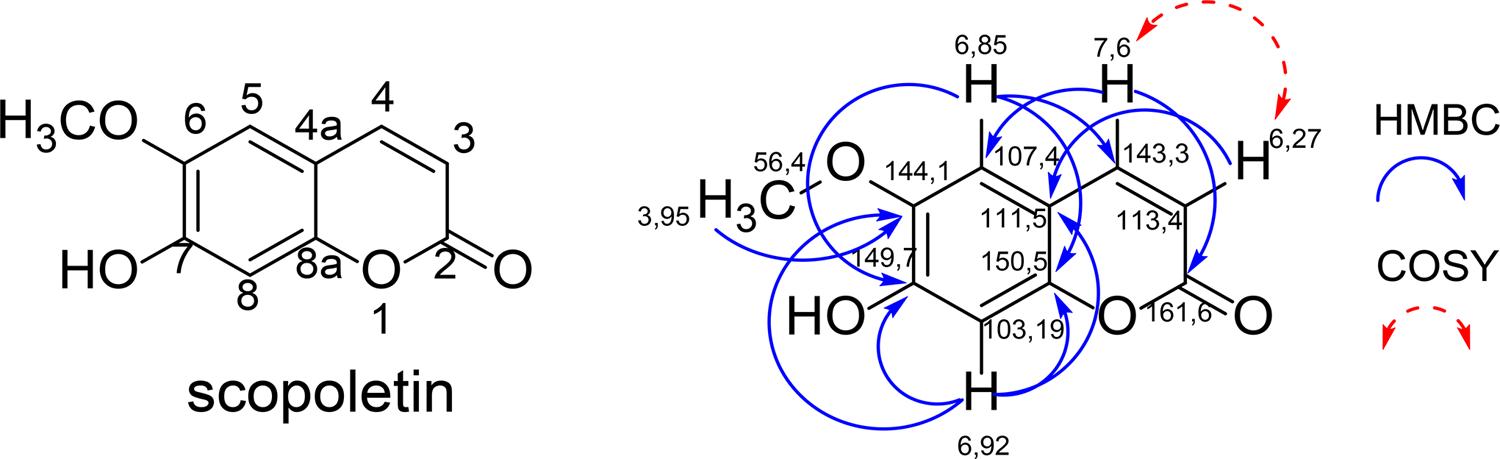

Scopoletin was obtained in the form of yellow crystals, showing an intense blue fluorescence under UV 365 nm light in TLC. Its structural characterization was identified by 1H and 13C NMR experiments and mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses, data were compared with the literature23,24. In HMBC, the methoxyl hydrogens in dH 3.95, showed only one correlation with the carbon in dC 144.1, nor even with the carbon in dC 149.7, characterizing that the methoxyl is in the C-6 position (FIGURE 2). This demonstrated that the structure corresponded to scopoletin and not to its isomer, isoescopoletin.

Data observed: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) d 3.95 (s, 3H, -OCH3 ), 6.92 (s, 1H, H-8), 6.85 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.27 (d, 1H, J 9.57 Hz, H-3), 7.60 (d, 1H, J 9.57 Hz, H-4); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) d 161.6 (C-2); 150.5 (C-8a), 149.7 (C-7); 144.1 (C-6); 143.3 (C-4); 113.4 (C-3); 107.4 (C-5); 103.2 (C-8); 56.4 (-OCH3); LC-MS (ESI) m/z, [M + H]+: 193.57; [M - H ]-: 191.57; mass: 192 u [C10H8O4].

This coumarin has been already isolated from some plants like Cordia insignis (Boraginaceae)25. In the Rubiaceae family, it may be found in the leaves of Morinda citrifolia26,27. As far as we know, this is the first report of coumarin in Warszewiczia genus.

Antimicrobial activity

Only the methanolic extract of leaves showed significant antimicrobial activity, against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida albicans, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus in the concentration of 1000 µg.mL-1 (TABLE 1).

According to the literature, Rahgozar and collaborators28 describe in their chemoinformatics-based study that in Warszewiczia coccinea, the triterpene sumaresinolic acid may show antimycobacterial activity because it has structural similarity with oleanolic acid, which has strong antimycobacterial synergism against Mycobacterium Bovis. However, so far there are no studies for the antimycobacterial activity of extracts, fractions, or metabolites isolated from W. coccinea.

Our phytochemical investigation may lead to the isolation of scopoletin. This coumarin demonstrates antimicrobial activity in the front of biofilms of Candida tropicalis and other pharmacological receptors29. However, other metabolites could be responsible for antimicrobial activity.

Antiangiogenic activity

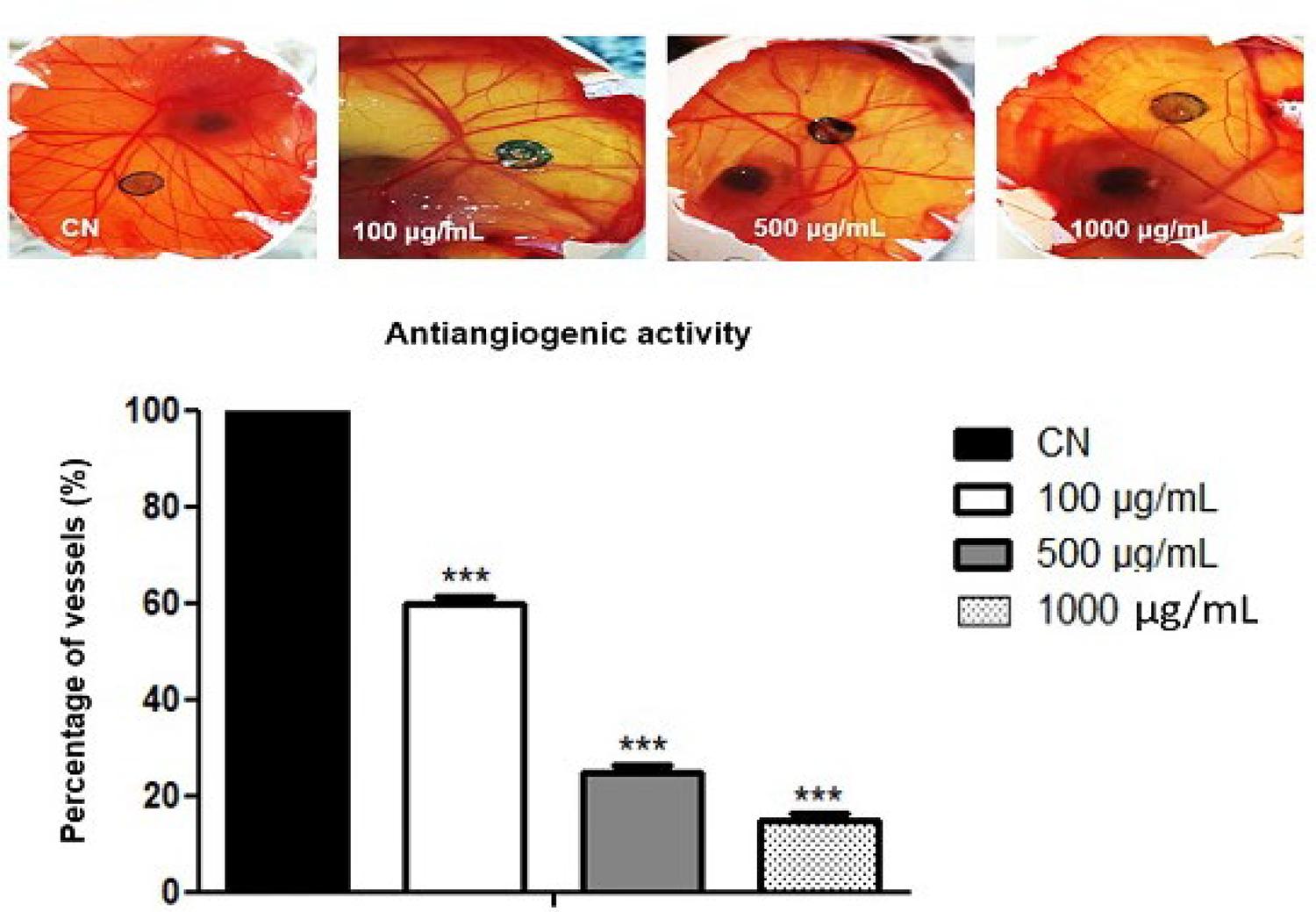

Through the angiogenic assay using the CAM models, it was possible to reveal the antiangiogenic and toxicity of the evaluated extracts. Both methanolic and hexanic extracts of leaves showed toxicity at all concentrations tested, with the viability of the negative control group. The hexanic extracts of branches demonstrate dose-dependent antiangiogenic activity was found. In this extract, vessel inhibition was observed with 40%, 70%, and 80%, to 100, 500, and 1000 µg.mL-1, respectively (FIGURE 3).

: Antiangiogenic activity of hexanic extract of branches. (n=3 ***) compared to Negative control (CN).

Despite the toxicity for Gallus domesticus embryos of methanolic and hexanic extracts of leaves, in these extracts because of the high toxicity, it was not possible to observe the angiogenic activity, being necessary to evaluate lower concentrations than 100 µg.mL-1. According to the recommendations of Nguyen, Shing, and Folkman19, the viability of embryos is necessary to describe the angiogenic activity, as well as the viability of the negative control for assay validation. However, containing such toxic substances is a very promising result in the search for antitumor substances. From these extracts, the 1H NMR and TLC showed terpenes, aromatics, and alkaloids evidence that might be the metabolites mainly responsible for the biological activity.

After the chromatography fractionation of the methanolic extract of leaves, it was possible to isolate the scopoletin, which has expressive antiangiogenic activity. This coumarin is present in extracts of leaves from Morinda citrifolia (Rubiaceae) and has been shown as a potential agent with an angiogenic suppressor, with no toxicity in healthy strains under cytotoxicity assays27. Furthermore, the scopoletin indicates promising interaction in silico of tumor vascularization factors, like VEGF-A, FGF-2, and ERK-1. In murine models, this metabolite shows inhibition of vascular formation in rat aorta and tumor growth30. The literature on the antiangiogenesis activity of scopoletin demonstrates the main role of this substance in front of tumoral vascularization, which may be useful in the inhibition of tumoral growth.

Conclusions

In the present study, we report the antimicrobial and antiangiogenic activity of leaves and branches from Warszewiczia coccinea (Vahl) Klotzsch. Among the active extracts, the methanolic extracts of the leaves showed antimicrobial activity including for a yeast strain: Candida albicans, the same extract showed toxicity in the angiogenesis assay (CAM). In addition, through TLC and 1H NMR analyses, we observe evidence of terpenes, aromatic substances, and alkaloids in leaves. After chromatography fractionation of the methanolic extracts of the leaves, it may be possible to isolate a bioactive substance: scopoletin. This is the first report of coumarin in the Warszewiczia genus.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Herbarium from the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia - INPA, and the Central Analítica do Laboratório Temático de Química de Produtos Naturais (CA-LTQPN - INPA) for the NMR and LC-MS analysis.

References

- 1 Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. Vol. 83, J Nat Prod. American Chemical Society; 2020. p. 770-803. [ https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285 ] [ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32162523 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285» http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32162523 - 2 Kurapati KRV , Atluri VS , Samikkannu T , Garcia G , Nair MPN . Natural products as Anti-HIV agents and role in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND): A brief overview. Front Microbiol. 2016; 6(Jan): 1-14. [ https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01444 ].

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01444 - 3 Simões CMO, Schenkel EP, Mello JCP de, Mentz LA, Petrovick PR. Farmacognosia do produto natural ao medicamento. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2017.

- 4 Costa CS de, Oliveira MN, Oliveira RJ de, Machado LL, Leão VK, Bueno MA. Antioxidant, Antibacterial Activities and Phytochemical Composition of the Aerial Parts, Stem and Roots of Gomphrena vaga Mart. from Northeast Brazil. Rev Virtual Quim. 2021; 13(6): 1345-52. [ https://doi.org/10.21577/1984-6835.20210075 ].

» https://doi.org/10.21577/1984-6835.20210075 - 5 Cardoso D , Särkinen T , Alexander S , Amorim AM , Bittrich V , Celis M , et al . Amazon plant diversity revealed by a taxonomically verified species list. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017; 114(40): 10695-700. [ https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706756114 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706756114 - 6 Bolzani VS, Young MCM, Furlan M, Cavalheiro AJ, Araujo AR, Silva DHS, et al. Secondary metabolites from Brazilian Rubiaceae plant species: chemotaxonomical and biological significance. Section Title: Pl Biochem. 2001; 5: 19-31. ISBN: 81-7736-048-5. [ https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=14194350 ].

» https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=14194350 - 7 Martins D , Nunez CV . Secondary metabolites from Rubiaceae species. Molecules. 2015; 20(7): 13422-95. [ https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200713422 ].

» https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200713422 - 8 Moreira VF, Vieira IJC, Braz-Filho R. Chemistry and Biological Activity of Condamineeae Tribe: A Chemotaxonomic Contribution of Rubiaceae Family. Am J Plant Sci. 2015; 06(16): 2612-31. [ https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2015.616264 ].

» https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2015.616264 - 9 Nunez CV, Vasconcelos MC. Novo Alcaloide Antitumoral de Duroia macrophylla. Patente: Privilégio de Inovação. Número do registro: PI10201203380, data de depósito: 31/12/2012, Instituição de registro: INPI - Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial. Brasil; PI10201203380, 2012.

- 10 Nunez CV, Santos P, Roumy V, Hennebelle T, Sahpaz S, Mesquita A, et al. Raunitidine isolated from Duroia macrophylla (Rubiaceae). Pl Med. 2009 Jul 21; 75(09): [ https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1234835 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1234835 - 11 Martins D, Nunez CV. Estudo químico e biológico de Duroia macrophylla Huber (Rubiaceae). Manaus. 2014. 250 f. Tese de Doutorado (Programa de Pós-graduação em Biotecnologia) - Universidade Federal do Amazonas, UFAM, Manaus. 2014. [ https://ppbio.inpa.gov.br/sites/default/files/Tese_MARTINS_D_2014.pdf ].

» https://ppbio.inpa.gov.br/sites/default/files/Tese_MARTINS_D_2014.pdf - 12 Cruz FS, Araújo MGP, Nunez CV. Leaves of Duroia longiflora: Isolation of a Biflavanoid and Histochemical Analysis. Nat Prod Commun. 2019; 14(6): [ https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578x19849779 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578x19849779 - 13 Céline V, Adriana P, Eric D, Joaquina AC, Yannick E, Augusto LF, et al. Medicinal plants from the Yanesha (Peru): Evaluation of the leishmanicidal and antimalarial activity of selected extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009; 123(3): 413-22. [ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.041 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.041 - 14 Radice M, Bravo L, Perez M, Cerda J, Tapuy A, Riofrío A, et al. Determinación de polifenoles en cinco especies amazónicas con potencial antioxidante. Rev Amaz Cienc Tecnol. 2017; 6(1): 55-64. [ https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6145606 ].

» https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6145606 - 15 Calderón AI, Simithy J, Quaggio G, Espinosa A, López-Pérez JL, Gupta MP. Triterpenes from Warszewiczia coccinea (Rubiaceae) as inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase. Nat Prod Commun. 2009; 4(10): 1323-6 [ https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578x0900401002 ] [ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19911564 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578x0900401002» http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19911564 - 16 Estevez Y, Castillo D, Pisango MT, Arevalo J, Rojas R, Alban J, et al. Evaluation of the leishmanicidal activity of plants used by Peruvian Chayahuita ethnic group. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007; 114(2): 254-9. [ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.007 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.007 - 17 Fachin-Espinar MT, Nunez. CV. Estudo Químico e Biológico de Warszewiczia schwackei (Rubiaceae). Manaus. 2019. 138f. Tese de Doutorado [Programa de Pós-graduação em Biotecnologia] - Universidade Federal de Amazônia, UFAM. Manaus. 2019. [ https://tede.ufam.edu.br/handle/tede/7689 ].

» https://tede.ufam.edu.br/handle/tede/7689 - 18 CLSI. M100-S25. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Second Informational Supplement Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Vol. 32, CLSI document M100-S16CLSI, Wayne, PA. 2015. 1-184 p.

- 19 Nguyen M, Shing Y, Folkman J. Quantitation of angiogenesis and antiangiogenesis in the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane. Microvasc Res. 1994; 47(1): 31-40. [ https://doi.org/10.1006/mvre.1994.1003 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1006/mvre.1994.1003 - 20 Falcão-Bücker NC. Efeito antitumoral e antiangiogênico de extratos bruto e supecrítico de Bidens Pilosa L. e Casearia sylvestris Swartz. Florianópolis. 2012. Dissertação de Mestrado (Programa de Pós-graduação em Farmácia) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, UFSC; Florianópolis. 2012. [ https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/96382 ].

» https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/96382 - 21 Lozano SA, de Sousa ABB, de Souza JC, da Silva DR, Salazar MGM, Halicki PCB, et al. Duroia saccifera: In vitro germination, friable calli and identification of ß -sitosterol and stigmasterol from the active extract against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Rodriguesia. 2020; 7. [ https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-7860202071054 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-7860202071054 - 22 Pedroza LS, Salazar MGM, Osorio MIC, Fachin-Espinar MT, Paula RC, Nascimento MFA, et al. Estudo químico e avaliação da atividade antimalárica dos galhos de Piranhea trifoliata. Revista Fitos. 2020; 14(4): 476-91. [ https://doi.org/10.32712/2446-4775.2020.905 ].

» https://doi.org/10.32712/2446-4775.2020.905 - 23 Shah MR, Shamim A, White LS, Bertino MF, Mesaik MA, Soomro S. The anti-inflammatory properties of Au-scopoletin nanoconjugates. New J Chem. 2014 Nov 1; 38(11): 5566-72. [ https://doi.org/10.1039/c4nj00792a ].

» https://doi.org/10.1039/c4nj00792a - 24 El-Demerdash A, Dawidar AM, Keshk EM, Abdel-Mogib M. Coumarins From Cynanchum Acutum. Rev Latinomer Quim. 2009; 1(November 2008): 65-9. [ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233817268_COUMARINS_FROM_CYNANCHUM_ACUTUM ].

» https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233817268_COUMARINS_FROM_CYNANCHUM_ACUTUM - 25 Correia FCS, Targanski SK, Bomfim TRD, Da Silva YSAD, Violante IMP, De Carvalho MG, et al. Chemical constituents and antimicrobial activity of branches and leaves of Cordia insignis (Boraginaceae). Rev Virtual Quím. 2020; 12(3): 809-16 [ https://doi.org/10.21577/1984-6835.20200063 ].

» https://doi.org/10.21577/1984-6835.20200063 - 26 Firmansyah A, Winingsih W, Manobi JDY. Review of scopoletin: Isolation, analysis process, and pharmacological activity. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2021; 11(4): 12006-19. [ https://doi.org/10.33263/BRIAC114.1200612019 ].

» https://doi.org/10.33263/BRIAC114.1200612019 - 27 Ahmadi N , Mohamed S , Sulaiman Rahman H , Rosli R . Epicatechin and scopoletin-rich Morinda citrifolia leaf ameliorated leukemia via anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenesis, and apoptosis pathways in vitro and in vivo. J Food Biochem. 2019; 43(7): 1-12. [ https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.12868 ] [ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31353737 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.12868» http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31353737 - 28 Rahgozar N, Khaniki GB, Sardari S. Evaluation of antimycobacterial and synergistic activity of plants selected based on cheminformatic parameters. Iran Biomed J. 2018 Nov 1; 22(6): 401-7. [ https://doi.org/10.29252/.22.6.401 ] [ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29510602 ].

» https://doi.org/10.29252/.22.6.401» http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29510602 - 29 Lemos ASO , Florêncio JR , Pinto NCC , Campos LM , Silva TP , Grazul RM , et al . Antifungal Activity of the Natural Coumarin Scopoletin Against Planktonic Cells and Biofilms From a Multidrug-Resistant Candida tropicalis Strain. Front Microbiol. 2020 Jul 7; 11. [ https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01525 ].

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01525 - 30 Tabana YM, Hassan LEA, Ahamed MBK, Dahham SS, Iqbal MA, Saeed MAA, et al. Scopoletin, an active principle of tree tobacco ( Nicotiana glauca ) inhibits human tumor vascularization in xenograft models and modulates ERK1, VEGF-A, and FGF-2 in computer model. Microvasc Res. 2016; 107: 17-33 [ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mvr.2016.04.009 ] [ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27133199 ].

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mvr.2016.04.009» http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27133199

-

Financing source:

The authors would like to thank the Brazilian research support agencies: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas (FAPEAM), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Fundação Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Ensino Superior (CAPES) for financial support and funding grants. CVN thanks CNPq for the productivity fellowship.

Publication Dates

- Publication in this collection

12 Mar 2025 - Date of issue

Feb 2025

History

- Received

10 Mar 2024 - Accepted

14 Aug 2024

Isolation of scopoletin and biological activities from Warszewiczia coccinea (Rubiaceae)

Isolation of scopoletin and biological activities from Warszewiczia coccinea (Rubiaceae)